Gastrointestinal: Non-neoplastic

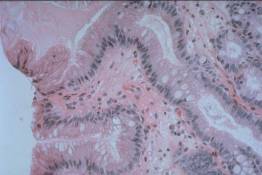

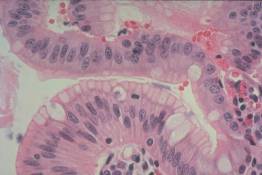

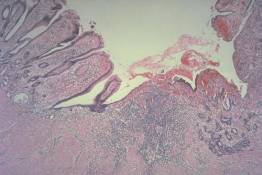

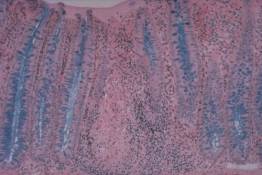

This is a photomicrograph of a biopsy taken from a patient who has Barrett's esophagus. Instead of the usual squamous lining, the esophagus has a columnar lining resembling that of the stomach.

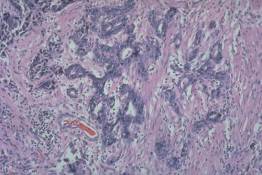

At higher power, the nature of the columnar lining can be seen. There are goblet cells, between which are cells that look like normal gastric surface cells. The goblet cells secrete acid mucin, which is not normally found in the stomach. Thus, this is not a normal type of gastric epithelium. It is this epithelium with a combination of goblet cells and gastric surface-like cells that predisposes the patient to the development of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

This gross photograph illustrates a squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in a patient who presented with progressive dysphagia. It is easy to see how this mass produced this symptom. The oval structure adjacent to the esophagus represents metatastic squamous cell carcinoma within a lymph node.

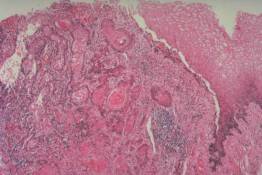

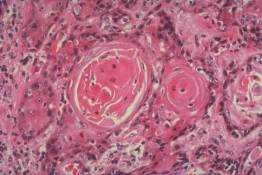

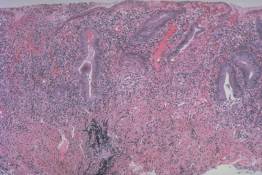

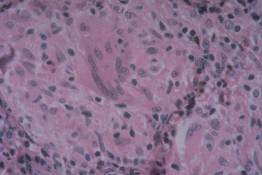

These are photographs showing the histologic appearance of the tumor illustrated in the previous slide. Note the junction between normal squamous epithelium and the malignant tumor in slide 4 and the higher power appearance of the tumor in slide 5. The whorled structures represent keratin pearls and indicate that this tumor is differentiating into structures recognizable as being of squamous origin.

These are photographs showing the histologic appearance of the tumor illustrated in the previous slide. Note the junction between normal squamous epithelium and the malignant tumor in slide 4 and the higher power appearance of the tumor in slide 5. The whorled structures represent keratin pearls and indicate that this tumor is differentiating into structures recognizable as being of squamous origin.

This gross photograph illustrates an ulcer in the antrum of the stomach. Based on this gross appearance alone, it is difficult to tell whether the ulcer is benign or malignant. Folds of gastric mucosa radiate up to the edge of the ulcer, an appearance typical of a benign peptic ulcer, but some of the folds have a nodular appearance, which is more suggestive of a malignant process.

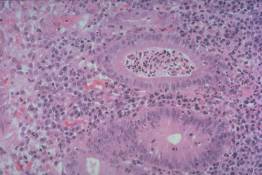

Slide 7 shows the ulcer crater illustrated in the previous slide. The actual crater is illustrated to the center and toward the right. The epithelium to the left represents regenerating gastric mucosa adjacent to the ulcer, while the epithelium seen to the right represents a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. On higher power (slide 8), the large, hyperchromatic nature of the nuclei forming the glands that are invading the ulcer bed can be seen.

Slide 7 shows the ulcer crater illustrated in the previous slide. The actual crater is illustrated to the center and toward the right. The epithelium to the left represents regenerating gastric mucosa adjacent to the ulcer, while the epithelium seen to the right represents a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. On higher power (slide 8), the large, hyperchromatic nature of the nuclei forming the glands that are invading the ulcer bed can be seen.

This photograph illustrates the characteristic appearance of the colon in a patient with ulcerative colitis. The entire colon is abnormal, and the usual transverse rugal folds have been almost completely effaced. Although the colon looks redder along the bottom (this is the proximal one-half), microscopic examination showed an almost equal degree of inflammation present throughout. Note that this colon is markedly shortened, measuring only about 60 cm. in length, relative to the normal length of close to 100 cm.

These photomicrographs illustrate the typical microscopic appearance of ulcerative colitis. Note the distortion of the crypt architecture and the marked chronic inflammation within the lamina propria (slide 10). Slide 11 shows a crypt abscess in which neutrophils are present within a crypt lumen. Note that the lamina propria contains many lymphocytes and plasma cells with only a few neutrophils. This is typical of ulcerative colitis.

These photomicrographs illustrate the typical microscopic appearance of ulcerative colitis. Note the distortion of the crypt architecture and the marked chronic inflammation within the lamina propria (slide 10). Slide 11 shows a crypt abscess in which neutrophils are present within a crypt lumen. Note that the lamina propria contains many lymphocytes and plasma cells with only a few neutrophils. This is typical of ulcerative colitis.

This colon was removed from a patient with Crohn's disease. In contrast to the diffuse, circumferential inflammation of ulcerative colitis, here the inflammation has produced large, irregularly shaped to rake-like ulcers that are separated from each other by mucosa that appears close to normal.

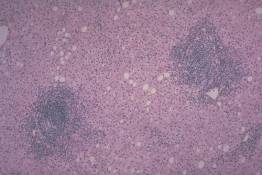

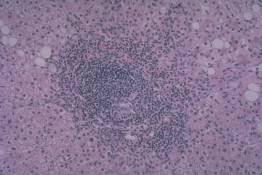

These slides illustrate the appearance of granulomas in a patient with Crohn's disease. Note that there is a compact aggregate of epitheloid histiocytes, recognized by their oval, elongated or slipper-shaped nuclei. Note the multinucleated giant cell near the center of the granuloma in slide 14.

These slides illustrate the appearance of granulomas in a patient with Crohn's disease. Note that there is a compact aggregate of epitheloid histiocytes, recognized by their oval, elongated or slipper-shaped nuclei. Note the multinucleated giant cell near the center of the granuloma in slide 14.

This photograph illustrates the appearance of chronic hepatitis in a biopsy taken from a patient with chronically elevated serum transaminases following an episode of hepatitis-B. The two structures heavily infiltrated by inflammatory cells are portal tracts. The inflammatory cells within the portal tracts extend into the parenchyma, effacing the junction between the portal tracts and the hepatic parenchyma (limiting plate). Also note the scattered inflammatory cells and mild fatty change in the hepatic parenchyma.

At higher power, the chronic inflammatory cells, mostly lymphocytes, can be seen extending into the parenchyma to produce the appearance of "piecemeal necrosis". Although no necrotic liver cells can actually be identified, liver cells have undergone necrosis as the portal tract has enlarged at the expense of the parenchyma. In the absence of inflammation or necrosis joining adjacent portal tracts, the prognosis is relatively favorable.